Sign up here to subscribe to the Grower2grower Ezine. Every two weeks you will receive new articles, specific to the protected cropping industry, informing you of industry news and events straight to your inbox.

Feb 2021

Greenhouse Cucurbits

The Last Word

GREENHOUSE CUCURBITS

Dr Mike Nichols

On the 13th of December 2019 the New Zealand Ministry of Primary Industries (MPI) advised the Queensland government of the suspension of imports of fresh cucurbits from Queensland due to the presence of Cucumber green mottled mosaic virus in a consignment of watermelons. At the current time this suspension still applies, and the price of cucurbits in New Zealand is of course considerably higher than normal because it is not possible to import the cheaper field grown produce and therefore the only product available in New Zealand must be grown under protective cultivation.

Of course, most of the cucumbers consumed in New Zealand are greenhouse grown in New Zealand, and have been for many years, and it is only the out of season zucchini, water melon and rock melon which are normally imported. This is not to say that these crops cannot be grown in greenhouses in New Zealand and in fact some 40 years ago there was considerable interest in the potential of producing rock melons as an export crop for the Japanese market.

Of course, in this respect New Zealand has one big advantage over Australia in that we are free from fruit fly and can export to Japan. At Massey University we grew a number of melon crops at that time both outside and in a high tunnel house and in heated green houses. More recently I grew seedless watermelons hydroponically in a heated greenhouse.

I have also seen crops of courgettes being produced here in greenhouses near Tauranga up strings, and clearly out of season. I suspect but this is a much more difficult crop to manage then melons or watermelons. The leaves are much larger, and brittle, and they really do not lend themselves to greenhouse production. The key to successful courgette production is regular harvesting, and the control of mildew.

How does one grow a cantaloupe in a greenhouse It certainly requires a considerable amount of training of the plants, but the basic philosophy is to grow them up a string to a height of about two metres, and to remove all the laterals and flowers up to the 9th or 10th leaves. Cantaloupes produce separate male and female flowers, and the male flowers develop mainly on the main stem and the female flowers on the lateral shoots. If the lateral shoots are only allowed to develop above the 9th or 10th main leaf, this is where the fruit will be formed. Therefore, everything produced in the axiles of the leaves up to that level are removed, lateral shoot and any male flowers and because there are plenty of male lowers produced further up the mainstem at the time when the female flowers are open. The laterals are stopped after 2 leaves, and because the fruit behaves as a very strong “sink” vegetative growth on the plant virtually ceases after pollination. The number of fruits allowed to mature per plant can then be decided, with surplus ones being removed.

My first attempt to pollinate the flowers with a small artists brush were a complete disaster—it became covered in nectar, so I reverted to using bumble bees, which did an excellent job. If the melons are then bagged into small nets, they can be harvested at optimum maturity for the particular market. Full slip for local and slightly less mature for more distant markets.

There are essentially two types of watermelon available, the standard seedy watermelon, of which the variety “sugar baby” is an excellent example, and the seedless type, which requires very special treatment if it is to be grown successfully. Seedless watermelon is always higher priced, because it is much more difficult to grow. Of course, how well it sells depend on whether one likes to swallow the almost non-existent seeds or prefers to spit out the black seeds from the conventional watermelon.

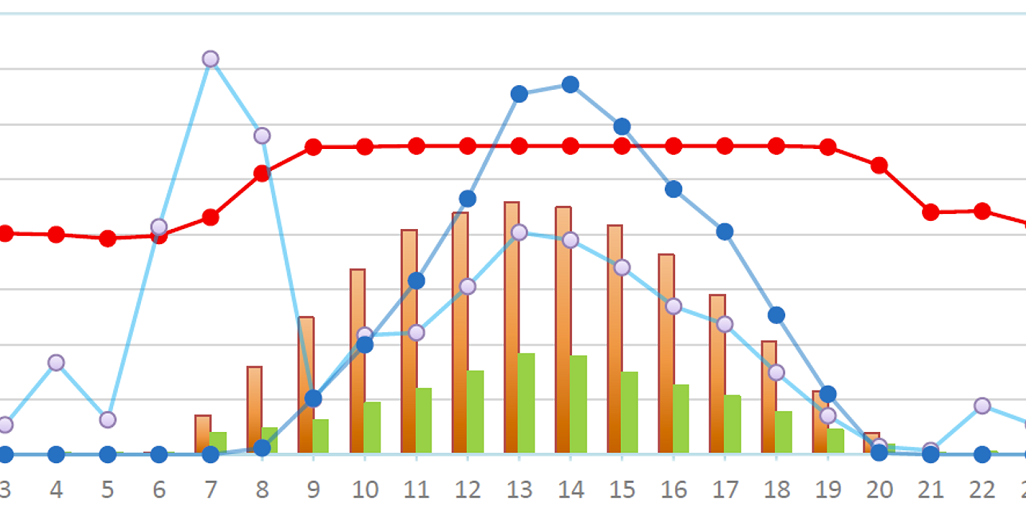

Watermelon are prone to some serious root borne diseases, and in many countries, they are grafted onto a disease resistant root stock. (See picture)

Seedless watermelons also require higher temperatures than standard varieties in order to germinate and grow. They also require a pollinator, because they are triploid (produced by crossing a tetraploid with a diploid plant), and are therefore self-sterile. This means that about 1/5 of the planting will need to be of a pollinator, which will have little or no economic value, however once the pollination has occurred then the pollinator can be removed to allow the triploid to fill the ground more effectively. Obviously using hydroponics is likely to produce a superior crop than the soil, and coir might provide the most suitable medium. I consider growing the watermelons up strings as being unworkable and allowing them to spread over the floor of the house the simplest training solution.

Pests such as spider mite can be a potential problem for cucurbits, but useful biological control methods (eg using Phytoseoelius for spider mites), can reduce the need for any spraying.

Harvesting is the next problem, and this requires experience, to ensure that the watermelon is mature, but not overmature. The drying of the tendril closest to the melon, the colour of the ground spot, and the sound of the melon when tapped are all useful means of knowing when to harvest.

Article written and supplied by Dr Mike Nichols

I appreciate your comments. Please feel free to comment on the grower2grower Facebook page:

https://www.facebook.com/StefanGrower2grower/

CLASSIFIED

Subscribe to our E-Zine

More

From This Category

Greenhouse Production in the Future – Mike Nichols

(Video of session now available) Excellent online webinar hosted by De Ruiter/Bayer Australia

An observation about Chlorosis effecting Tomato Plants.

Design a Semi Closed Greenhouse with Hortinergy

Direct Air Capture (DAC) is now a reality— Onsite CO2 generation scalable for both large and small operations