Know Your, Papaya, Bananas & Other Tropical Fruits

By Dr Mike Nichols

Replacing imports with domestic produce reduces NZ’s import dependency, carbon footprint, improves food security, and critically reduces the biosecurity risk of bringing into the country dangerous pests, diseases etc. The areas in NZ capable of subtropical fruit growing are expanding, enabling new land use opportunities for regional development and employment. Our locally grown bananas and pineapples can be produced without sprays or fumigants, unlike imported fruit.

In NZ many different banana varieties can be grown, some are citrusy, others creamy-tasting and although smaller they are a convenient size for schoolbags and lunch boxes. Likewise, locally grown pineapple types range from a smaller and more tender Queen (Laurenson, 2021) through to the larger more acidic Red and Cayenne type pineapples. There is an increasing interest in the production of papaya in greenhouses for the local market, as well as other tropical fruits.

Bananas:

Bananas are the most important fruit crop in the world. Over 114 million tonnes are produced every year (compared with apples – 87 million tonnes). In simple terms 50% of the bananas are produced in Asia, with India (30 million and China (11 million) tonnes being the major producers, with virtually all this fruit is consumed domestically. The Americas produce a further 30% of the world bananas, and the rest is grown mainly in Africa (usually in small holdings) while the South Pacific and Europe barely warrant a mention.

Apples can be considered to be a fairly well researched crop, and although there is still considerable room for improving productivity (for example the development of the 2-dimensional apple system by Dr S Tustin, which will lend itself to robotic harvesting) such production enhancements have been due to the gradual increase in our knowledge of apple crop physiology, or “what makes the plant tick”.

When I became interested in the potential of growing bananas in New Zealand my first approach was to investigate the scientific literature on what was known about banana crop physiology. The result was a most disturbing. There was only one single research paper on the subject. (Turner et al, 2007)

The problem would appear to be that in the tropics the major problems were diseases (frequently spread by planting up infected plant material into a clean site). Tissue culture has assisted in reducing this problem, but it could be a concern if a new industry is developed in New Zealand. Certainly, all new plant introductions from outside New Zealand must come through a rigid biosecurity system, and we certainly don’t want any plants to arrive on yachts from the Pacific Islands!!!

The “Green Revolution” which more than doubled cereal (wheat and rice etc) yields in many developing countries, including Mexico, India, Philippines owes much to our basic understanding of crop physiology. In simplistic terms it was established that the existing varieties tended to lodge when provided with fertilizer to produce increased yield, (resulting in crop losses) but by using dwarf varieties remained upright when using fertilizer and thus produced considerably enhanced yields.

Banana is an interesting plant in that we do not even understand what causes the plant to initiate flowers. A key factor because without floral initiation we can have no crop. There is not a very good market for banana leaves! It appears that flower initiation is varietal dependant—some varieties require many more leaves than others before they will initiate flowers.

The banana is day neutral for floral induction, but photoperiods of less than 12 h are associated with a slowing in the rate of bunch initiation that is independent of temperature expressed as growing degree days. This may contribute to seasonal variations in banana flowering, even in more tropical environments with moderate temperatures. We know considerably more about the postharvest requirements of bananas than how to grow them. This is probably because this is the only time, we (as consumers) can exert any real influence on outcomes.

Although the banana grows to a height of several (3-5) metres it is not a tree.

The flowers are actually initiated close to the ground within the corm (so called), where all the leaves are also initiated. The so-called stem of a banana ”tree” is actually leaf structure.

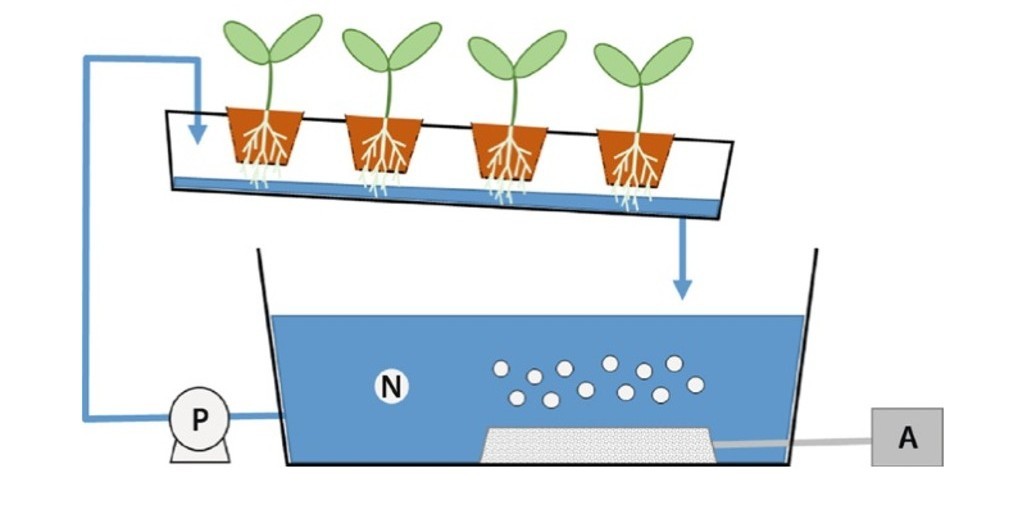

The only two important facts that appear to relate to the growth of bananas is the leaves are easily damaged by the wind, and this severely reduces their photosynthetic capability, and that moisture stress (which causes the leaves to droop) is also a major reduction in photosynthesis. Clearly there is a huge advantage of having good shelter—and a greenhouse is even better as it provides slightly warmer conditions in a sub optimal country for bananas like New Zealand. It would appear more than likely that a hydroponics system would be better than growing in the soil, because of the potential for superior moisture and nutrient management. However, this is unknown, because few bananas have every been grown in greenhouses hydroponically.

We also do not even know what determines the number of leaves required before the banana plant will initiate flowers, or even whether this is firmly fixed genetically, and simply varies according to variety. With most important crop plants, we understand (at least in simple terms) what causes them to flower, but this information is not available for the most important fruit crop in the world!!!

The interest in establishing a banana industry in New Zealand is increasing, and one of the major constraints — the availability of a relatively cheap but tall greenhouse appears to have been overcome, with the development of the Haygrove Terrace Tunnel. A 7 m tall greenhouse, essentially like a standard Haygrove tunnel, but on 4 m high legs.

.jpg)

Pineapples:

Currently virtually all the pineapples grown in New Zealand are grown in the field, on sites with particularly warm microclimates. (Laurenson, 2021). Finding a suitable microclimatic site, with a suitable soil type is not straight forward. Using protected cultivation methods (greenhouses) would significantly enhance productivity, as would the use of hydroponics. Heating the greenhouse, when necessary, would provide more ripe pineapples during the winter and thus ensure year-round production. New Zealand is fortunate to have considerable geothermal areas, which could well be used for growing such crops.

Mango:

Why no one has seriously considered growing mango in New Zealand leaves me stumped. The possibility of using dwarf root stocks and high tunnels and using drought dormancy to establish year-round production, has the potential to eliminate the need to import mango, and their biosecurity risk.

Papaya:

Papaya production is now well established as a greenhouse crop in southern Spain (in plastic houses in Almeria), and there is now a greenhouse crop growing at Venlo in the Netherlands. There are now several small plantings being established in New Zealand, both for fruit production, and also for medicinal use.

Marketing of tropical fruit:

Of course, growing a crop, of any description, is only half the battle. The crop has to reach the consumer by some means or other. Until recently most locally produced tropical fruit was sold face to face at farmer’s markets, and farm stalls. These markets are not always convenient for busy consumers who prefer one-stop shopping. Also, these face-to-face market fruit sales do not necessarily require NZGAP certification nor Food Act registration whereas produce sold via supermarkets and wholesalers does. See article from Kotare sub tropicals. news/post/new-zealand-grown-subtropicals-nzgap-certified/

References

Laurenson, W (2021) “Pineapple harvest in Northland”. The Orchardist, 94 (4), 26-27.

Turner, D., Fortescue, J., & Thomas, D. S. (2007). Environmental physiology of the bananas (Musa spp.). Brazilian Journal of Plant Physiology, 19(4), 463-484

I appreciate your comments. Please feel free to comment on the grower2grower Facebook page:

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)